The phrase “value proposition” has been printed on pitch decks and websites for decades, yet it remains one of the most misunderstood ideas in modern business. In practice, it rarely announces itself in bold type or tidy slogans. It tends to reveal itself in quieter ways: in why a customer returns after a first purchase, in why a prospect hesitates even when the price is right, or in why two companies offering almost identical services experience very different outcomes.

In the UK, where markets are mature and competition is rarely naive, the absence of a clear value proposition is usually disguised as something else. Leaders talk about margin pressure, customer churn, or “needing more leads,” when the real issue is simpler and harder to admit. The business has not articulated, even internally, why it deserves to exist alongside its peers.

I’ve seen this play out in boardrooms where everything looked robust on paper. Revenues were steady, the product worked, the staff were capable. Yet when someone asked why a customer should choose this firm rather than the one down the road, the answers drifted into descriptions rather than reasons. Longer opening hours. Friendly service. Quality materials. All true, and all forgettable.

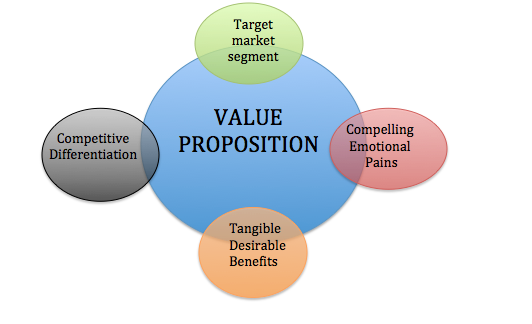

The distinction between a USP for business and a value proposition is often blurred, particularly in UK SMEs. A USP is usually framed as a feature or claim, something that can be placed on a banner or landing page. A value proposition goes further. It explains the outcome a customer can expect, the problem that quietly disappears once the business is chosen, and the trade-off the company has deliberately decided to make.

Trade-offs are where clarity begins, and also where discomfort creeps in. A business that tries to be fast, cheap, bespoke, and premium at the same time is not being ambitious; it is being evasive. Clear value propositions require exclusion. They require a willingness to say no to certain customers, certain projects, and certain forms of growth.

In the early 2010s, many UK professional services firms expanded rapidly by broadening their offer. Strategy consultancies added delivery. Agencies added software. Software firms added consulting. For a while, growth masked confusion. Then clients began asking sharper questions. Why this firm, for this job, at this price? Those without a grounded answer found themselves competing on discounts rather than relevance.

What often triggers a serious look at value proposition explained UK-style is a moment of unease. A lost contract that “should have been ours.” A new competitor winning work without undercutting on price. A customer who leaves and cannot quite articulate why. These moments linger because they suggest something structural rather than tactical.

The most effective value propositions I’ve encountered were not written by marketing teams in isolation. They emerged from uncomfortable conversations between sales, delivery, and leadership. Sales teams explained what prospects actually reacted to, not what they were supposed to care about. Delivery teams admitted which types of work consistently created friction. Leadership acknowledged constraints that could not be engineered away.

At its core, a value proposition answers three questions with discipline. Who is this for, specifically. What problem does it solve better than alternatives. Why is this business uniquely positioned to solve it, even if that uniqueness feels unglamorous. The answers are rarely elegant sentences at first. They start as messy paragraphs and half-agreed phrases.

I once watched a founder cross out an entire positioning statement after realising it described the company they wished they were running, not the one customers were actually paying for.

UK businesses often underestimate how context-sensitive value propositions are. What resonates in London’s financial services sector may sound hollow in a manufacturing corridor outside Birmingham. Procurement-led buyers listen for risk reduction and compliance. Founder-led SMEs listen for trust and speed. Consumers listen for reassurance, often between the lines rather than in claims.

This is where observation matters more than frameworks. Sitting in on sales calls. Reading support tickets. Watching how customers describe the business when they are not being prompted. Language used by customers is usually plainer and more revealing than anything produced internally.

Another overlooked element is time. Value propositions are not static declarations. They evolve as markets mature and expectations rise. What felt distinctive five years ago may now be table stakes. Free delivery, next-day response times, cloud-based access. These were once differentiators; now they are assumed. Businesses that fail to revisit their value proposition often discover too late that they are competing on yesterday’s advantages.

There is also a cultural hesitation in many UK firms to articulate ambition too clearly. A fear of sounding arrogant, or of making promises that invite scrutiny. Yet vagueness does not protect credibility; it erodes it. Customers are more sceptical of safe language than of specific claims that can be tested.

A clear value proposition is not about being louder. It is about being precise. It shows up in pricing models that align with outcomes rather than hours. In onboarding processes that prioritise what matters most to the customer, not what is easiest for the business. In marketing that explains trade-offs openly rather than burying them in footnotes.

Interestingly, some of the strongest value propositions are almost invisible externally. They are felt rather than stated. A logistics firm that never misses a delivery window. A software provider whose updates never disrupt operations. A consultancy that refuses work outside its core competence. These decisions compound quietly, building a reputation that no tagline could replicate.

Defining a value proposition, properly, forces a business to confront itself. Its constraints, its habits, its real strengths. That confrontation can be uncomfortable, particularly for founder-led organisations where identity and strategy are intertwined. But without it, growth becomes reactive rather than deliberate.

In an environment where customers have more choice and less patience, clarity is not a branding exercise. It is an operational discipline. The businesses that articulate their value proposition clearly are not necessarily more creative or better funded. They are simply more honest about who they are for, and who they are not.